Every Child Matters!

What were residential schools or “Indian Schools”?

These were boarding schools for Indigenous children, that didn’t exist just to teach them school subjects, but “primarily to break their link to their culture and identity,” according to the Commission’s report.

“When the school is on the reserve or reservation, the child lives with its parents, who are savages; he or she is surrounded by savages, and though they may learn to read and write their habits, and training and mode of thought are Indian. They are simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly pressed on myself, as the head of the Department, that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.”

Opened in 1879 in Pennsylvania, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School was the first government-run boarding school for Native Americans. Civil War veteran Lt. Col. Richard Henry Pratt spearheaded the effort to create an off-reservation boarding school with the goal of forced assimilation. The Army transferred Carlisle Barracks, a military post not in regular use, to the Bureau of Indian Affairs for use as a boarding school.

Students were forced to cut their hair, change their names, stop speaking their Native languages, convert to Christianity, and endure harsh discipline including corporal punishment and solitary confinement. This approach was ultimately used by hundreds of other Native American boarding schools, some operated by the government and many more operated by churches.

Pratt, like many others at that time, believed that the only hope for Native American survival was to shed all native culture and customs and assimilate fully into white American culture. His common refrain was “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.”

Carlise “Indian” School

About 20 years ago, Earl and I visited the Carlise “Indian” School in Carlise Pennsylvania. It was then and still is now a active military base. The base has been used for a variety of things over its history. Prior to the “Indian” school it was last uses by the military for housing soldiers,

Physical and sexual flourish more often than not occurred all over Turtle Island at the schools. Outright murder was common. Children were seen as disposable not human by the Governments of both the USA and Canada and The Catholic Church Nuns and Priests. Records show that everything from speaking an Aboriginal language, to bedwetting, running away, smiling at children of the opposite sex or at one’s siblings, provoked whippings, strappings, beatings, and other forms of abuse and humiliation and abuse as well as rape.

According to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, the United States also had more than 350 government-funded boarding schools across the US.

In Canada, the Indian residential school system was a network of mandatory boarding schools for Indigenous peoples. The network was funded by the Canadian government‘s Department of Indian Affairs and administered by Christian churches. The school system was created to remove Indigenous children from the influence of their own culture and assimilate them into the dominant Canadian culture. Over the course of the system’s more than hundred-year existence, around 150,000 children were placed in residential schools nationally. By the 1930s about 30 percent of Indigenous children were believed to be attending residential schools. The number of school-related deaths remains unknown due to incomplete records. Estimates range from 3,200 to over 30,000

Why our kids need to learn about residential schools

For more than a century, kids were systematically removed from their homes and sent to residential schools where they were forbidden to speak their language or practice their culture. But how do we all talk about Canada’s and the USA’S cultural genocide with ourselves, our kids and each other today?

A SURVIVOR! Why we wear Orange!

Phyllis Webstad is Northern Secwpemc (Shuswap) from the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation (Canoe Creek Indian Band). She comes from mixed Secwepemc and Irish/French heritage, was born in Dog Creek, and lives in Williams Lake, BC. Today, Phyllis is married, has one son, a step-son and five grandchildren. She is the Executive Director of the Orange Shirt Society, and tours the country telling her story and raising awareness about the impacts of the residential school system. She has now published two books, the “Orange Shirt Story” and “Phyllis’s Orange Shirt” for younger children.

I went to the Mission for one school year in 1973/1974. I had just turned 6 years old. I lived with my grandmother on the Dog Creek reserve. We never had very much money, but somehow my granny managed to buy me a new outfit to go to the Mission school. I remember going to Robinson’s store and picking out a shiny orange shirt. It had string laced up in front, and was so bright and exciting – just like I felt to be going to school!

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada is mandated to operate for five years, during which time it will document the history of the schools and their consequences and publicize survivors’ testimony and memories. At the end of its work, the commission will issue a report that includes recommendations to all involved parties, including the state, churches, the public, and survivors. Of course, we cannot know the content of recommendations until they are written, but we can expect suggestions to range from demands for improved social services to recommendations for criminal prosecutions.

The government of Canada now identifies 136 institutions as former Indian Residential Schools that were established exclusively for Aboriginal children by the federal government in partnership with the country’s four major churches. The schools operated for approximately 100 years, with the final schools closing as recently as 1998. Canadian law made attendance at the schools mandatory for all Aboriginal children and made the school administration the legal guardians of the children who attended. At the time the truth commission was established, there were between 105,000 and 150,000 people living in Canada who went to residential school as children, about 10 percent of the present-day Aboriginal population.

There are no records accurately showing what proportion of aboriginal children were taken from their families, but there is no question that every Aboriginal community in Canada today is affected by the experience of residential school. In addition to the untold suffering of direct survivors of the schools, the system continues to have devastating impacts on Aboriginal young people. The intergenerational experiences of a mass atrocity are felt when the damage done to one generation perpetuates in the lives of the next. Residential schools sought to interfere with the closest relationships in Aboriginal communities by taking children as young as four away from their parents, relatives, and community life. The consequences of this policy on family life are still felt across the country today. After three consecutive generations of families who suffered the theft of their children, today’s youth is the only living generation of Aboriginal people to grow up in a country where the state permits them the care of their own parents. Add to this toll the crime that humanity’s collective heritage is rendered immeasurably poorer by the loss of language, knowledge, culture, and life that the schools inflicted.

The history of residential schooling remained hidden for decades by people in the dominant society who called survivor testimony over-exaggerations or isolated cases in an otherwise normal education system. Although the residential school system is a proven cause of widespread human rights violations and continues to have damaging effects on First Peoples all across the country, until quite recently few efforts were made to address the damage done. The catalyst for change happened in 1993, when then-National Chief Phil Fontaine appeared on the national news and made a statement recounting the physical and sexual abuse that occurred at his school as a child. The statement opened a floodgate of legal action, with thousands of cases filed against the state for similar experiences of abuse at the schools. The influx of cases threatened to overwhelm the judicial system and pushed the government to agree on a negotiated settlement to the massive class-action lawsuit filed against it. This settlement included an extensive compensation program for survivors of the school system, as well as the establishment of a National Truth and Reconciliation Commission. As the first national truth commission to ever be established as a result of successful legal action taken against a state guilty of mass human rights violations, the Canadian truth commission represents a victory over denial.

The commission, which is still at the beginning of its five-year mandate, will research and report on the experiences and legacies of residential school through the direct testimony of former students, staff, their families, and their communities, and through the work of a national research center. The mandate of the truth commission includes extensive provisions that ensure the process embraces a flexible and holistic approach to research, statement giving, and commemoration.

For all its successes, the truth commission remains a controversial approach to dealing with the past in Canada. Particularly controversial is a restriction that prohibits survivors and staff from naming or otherwise identifying individuals accused of wrongdoing. In principle such restrictions are offensive in the mandate of a truth commission, but the logic in this case is intended to protect the rights of victims. The truth commission in Canada resulted from a civil lawsuit, not a criminal proceeding, and the difference is crucial: as a civil process, the truth commission does not affect criminal liability. Perpetrators of crimes at residential school are in no way protected from future prosecutions. As a body that will research and collect information pertaining to terrible abuses, the truth commission must be careful to operate in a way that will support, not interfere with, future criminal proceedings. Although it is not clear that publicly naming names would pose a serious risk in this regard, there is enough at stake to justify taking special precautions, and the restriction against publicly naming perpetrators serves as an extra protection against potentially hindering future criminal prosecutions.

Is the truth and reconciliation commission the answer to a century-long demand for justice for the crimes of Indian Residential Schools? No. Justice for the past means many things and takes many forms; a truth commission is one small piece of that greater goal. What the truth commission can accomplish, and has already begun to achieve, is to make a space where survivors can finally speak the truth and be heard.

What were conditions like?

Residential school students were subject to physical and sexual abuse by staff, were often malnourished or underfed, and lived in poor housing conditions that threatened their safety, according to the TRC reports. Infectious diseases like tuberculosis and influenza often ran rampant among the students, leading to

PHYSICAL: Physical abuse did flourish. Records show that everything from speaking an Aboriginal language, to bedwetting, running away, smiling at children of the opposite sex or at one’s siblings, provoked whippings, strappings, beatings, and other forms of abuse and humiliation.

In Canada, the Indian residential school system[ was a network of mandatory boarding schools for Indigenous peoples. The network was funded by the Canadian government‘s Department of Indian Affairs and administered by Christian churches. The school system was created to remove Indigenous children from the influence of their own culture and assimilate them into the dominant Canadian culture. Over the course of the system’s more than hundred-year existence, around 150,000 children were placed in residential schools nationally. By the 1930s about 30 percent of Indigenous children were believed to be attending residential schools. The number of school-related deaths remains unknown due to incomplete records. Estimates range from 3,200 to over 30,000. Hundreds are found daily, and now places have even begun or think about digging. As of the end of June 2021, there were 751 unmarked or unknown graves found and growing.

According to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, the United States also had more than 350 government-funded boarding schools across the US.

Why we all need to learn about residential and Indian schools.

For more than a century, kids were systematically removed from their homes and sent to residential schools where they were forbidden to speak their language or practice their culture. But how do you talk about Canada’s cultural genocide with kids today? Teachers are finding some effective ways.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada is mandated to operate for five years, during which time it will document the history of the schools and their consequences and publicize survivors’ testimony and memories. At the end of its work, the commission will issue a report that includes recommendations to all involved parties, including the state, churches, the public, and survivors. Of course, we cannot know the content of recommendations until they are written, but we can expect suggestions to range from demands for improved social services to recommendations for criminal prosecutions.

The government of Canada now identifies 136 institutions as former Indian Residential Schools that were established exclusively for Aboriginal children by the federal government in partnership with the country’s four major churches. The schools operated for approximately 100 years, with the final schools closing as recently as 1998. Canadian law made attendance at the schools mandatory for all Aboriginal children and made the school administration the legal guardians of the children who attended. At the time the truth commission was established, there were between 105,000 and 150,000 people living in Canada who went to residential school as children, about 10 percent of the present-day Aboriginal population.

There are no records accurately showing what proportion of aboriginal children were taken from their families, but there is no question that every Aboriginal community in Canada today is affected by the experience of residential school. In addition to the untold suffering of direct survivors of the schools, the system continues to have devastating impacts on Aboriginal young people. The intergenerational experiences of a mass atrocity are felt when the damage done to one generation perpetuates in the lives of the next. Residential schools sought to interfere with the closest relationships in Aboriginal communities by taking children as young as four away from their parents, relatives, and community life. The consequences of this policy on family life are still felt across the country today. After three consecutive generations of families who suffered the theft of their children, today’s youth is the only living generation of Aboriginal people to grow up in a country where the state permits them the care of their own parents. Add to this toll the crime that humanity’s collective heritage is rendered immeasurably poorer by the loss of language, knowledge, culture, and life that the schools inflicted.

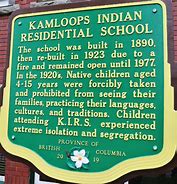

Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada

The history of residential schooling remained hidden for decades by people in the dominant society who called survivor testimony over-exaggerations or isolated cases in an otherwise normal education system. Although the residential school system is a proven cause of widespread human rights violations and continues to have damaging effects on First Peoples all across the country, until quite recently few efforts were made to address the damage done. The catalyst for change happened in 1993, when then-National Chief Phil Fontaine appeared on the national news and made a statement recounting the physical and sexual abuse that occurred at his school as a child. The statement opened a floodgate of legal action, with thousands of cases filed against the state for similar experiences of abuse at the schools. The influx of cases threatened to overwhelm the judicial system and pushed the government to agree on a negotiated settlement to the massive class-action lawsuit filed against it. This settlement included an extensive compensation program for survivors of the school system, as well as the establishment of a National Truth and Reconciliation Commission. As the first national truth commission to ever be established as a result of successful legal action taken against a state guilty of mass human rights violations, the Canadian truth commission represents a victory over denial.

The commission, which is still at the beginning of its five-year mandate, will research and report on the experiences and legacies of residential school through the direct testimony of former students, staff, their families, and their communities, and through the work of a national research center. The mandate of the truth commission includes extensive provisions that ensure the process embraces a flexible and holistic approach to research, statement giving, and commemoration.

For all its successes, the truth commission remains a controversial approach to dealing with the past in Canada. Particularly controversial is a restriction that prohibits survivors and staff from naming or otherwise identifying individuals accused of wrongdoing. In principle such restrictions are offensive in the mandate of a truth commission, but the logic in this case is intended to protect the rights of victims. The truth commission in Canada resulted from a civil lawsuit, not a criminal proceeding, and the difference is crucial: as a civil process, the truth commission does not affect criminal liability. Perpetrators of crimes at residential school are in no way protected from future prosecutions. As a body that will research and collect information pertaining to terrible abuses, the truth commission must be careful to operate in a way that will support, not interfere with, future criminal proceedings. Although it is not clear that publicly naming names would pose a serious risk in this regard, there is enough at stake to justify taking special precautions, and the restriction against publicly naming perpetrators serves as an extra protection against potentially hindering future criminal prosecutions.

Is the truth and reconciliation commission the answer to a century-long demand for justice for the crimes of Indian Residential Schools? No. Justice for the past means many things and takes many forms; a truth commission is one small piece of that greater goal. What the truth commission can accomplish, and has already begun to achieve, is to make a space where survivors can finally speak the truth and be heard.

What were conditions like?

Residential school students were subject to physical and sexual abuse by staff, were often malnourished or underfed, and lived in poor housing conditions that threatened their safety, according to the TRC reports. Infectious diseases like tuberculosis and influenza often ran rampant among the students, leading to many deaths.

When did the schools close?

Residential schools are not just artifacts from long ago. The last residential school in Canada closed in 1996, meaning that there are many survivors who are still dealing with the effects. The last “Indian” School closed in the USA in 1978.

A Personal prospective and story!

About 20 years ago, Earl and I visited the Carlise “Indian” School in Carlise Pennsylvania. It was then, and still is now an active military base. The base has been used for a variety of things over its history. Prior to the “Indian” school it was last used by the military for housing soldiers. When we visited it was prior to 911 and there were more options of getting onto the base then there is now. We were walking the grounds on a self-tour, and one of the buildings we passed had no markings. It was a sold brick building maybe 6 ft x 10 ft no windows and big wood door with wood hinges and a wood lock. We went over to it and I tried the door; it was open. The door swung open and inside was a cold dank room, with a dirt floor. Nothing was in it. Including no sunlight from the beautiful day because of the lack of windows. As soon as I stepped in I because nauseous, and dizzy. Earl grabbed me and took me back outside. We finished the tour and while walking back, we encountered a soldier that worked there. I asked him what the building was and he got quiet. He said it was a powder keg or a gun powder storge building used during the civil war. He then looked around and said to us. This building was used to punish the “Indian” children. I said what do you mean? He said when children did not behave liked the attendants wanted them to, they were thrown in here. No light, no blanket, no water or food. Just dank cold darkness for days on end for Punishment. Many children died in there and some were never the some were never the same when they did come out. I have never been the same since that visit. I always remember my lost brothers and sisters of that school. We don’t not hold you accountable for what happened in the past, but we do hold you accountable for the future. This atrocity needs be talked about and dealt with and the USA and Canadian governments along with catholic church needs to acknowledge what happen and help us rebuild out future with the survivors, the memory and our people’s future and we need each of you to help us with that.

By now, you’ve probably heard of the hundreds of unmarked graves discovered at “Indian Schools” in Canada.

What you may not know is that hundreds of these schools operated throughout the US and Canada, and it may not even be possible to count how many Native children were killed in them.

The Indian Boarding School Policy was started using the Indian Civilization Act Fund of 1819, with the intention of “assimilating” Native Americans into White society.

Let me say that again: the explicit purpose of Indian Schools was to take Native children, and “assimilate” them into being White children.

From then until as late as the 1990s, Native children were forcibly taken from their homes under threat of violence, and put into hundreds of different boarding schools across the country. These children were forbidden from practicing their culture, including speaking their native tongue, and had to adopt White Christian culture.

Again, the purpose of these schools wasn’t just to turn Natives into Christians, but to turn them into White Christians.

A common sentiment in the US government was that it was necessary to “kill the Indian and save the man”, meaning that the only way for Natives to thrive was to destroy their society and culture, and convert them into being White. This was based on the racist idea that Natives were similar enough to Whites to deserve being equal to them, but only after every aspect of what made them Native was eradicated.

And it didn’t matter how many of them had to die to accomplish this.

The living conditions of these schools were terrible, and they were often infested with influenza, mumps, measles, chickenpox, and tuberculosis. Children died often from sickness, as well as from abuse, neglect, and even murder.

Although these tragedies were known by local tribes through oral stories, investigations are just beginning to reveal mass unmarked graves holding the bodies of children as young as 3 years old.

The exact number of how many boarding schools that were built, as well as how many children were forced to attend, was never reported, so we only have rough estimates to reference.

What we do know is that 7 schools have been searched and more than 1,500 bodies of children have been found.

As more and more former Indian Schools, and dead children, are uncovered, this is looking more and more like the closest thing to the concentration camps of the holocaust that we’ve ever had on this continent. And it was done exclusively to children.

It is no wonder that the Bureau of Indian Affairs, who continues to routinely infringe on the rights and livelihoods of Natives, admitted over 20 years ago that it had committed, as they put it, “ethnic cleansing and cultural annihilation”.

I want to be very clear, and avoid hyperbole in this statement: the US government created a program in the early 1800s with the express intent of converting Natives to Whiteness, and spent over 150 years stealing Native children and putting them into “schools” where they were stripped of their culture, name, identity, language, and religion, subjected to abuse, neglect, disease, and sometimes murder, and we may never know how many thousands of them died as a result.

It is imperative that we end the Bureau of Indian Affairs, grant full sovereignty to the Native tribes in this country, give them back as much of the federal and state-held lands that were taken from them as possible, and ensure that nothing like this ever happens again.